Landscape charity looking for a new leader

Cornwall National Landscape Trust are looking for a new Chairperson to lead the charity which supports the protected landscape in Cornwall. The Trust are looking for a Chair that possesses...

James Richards

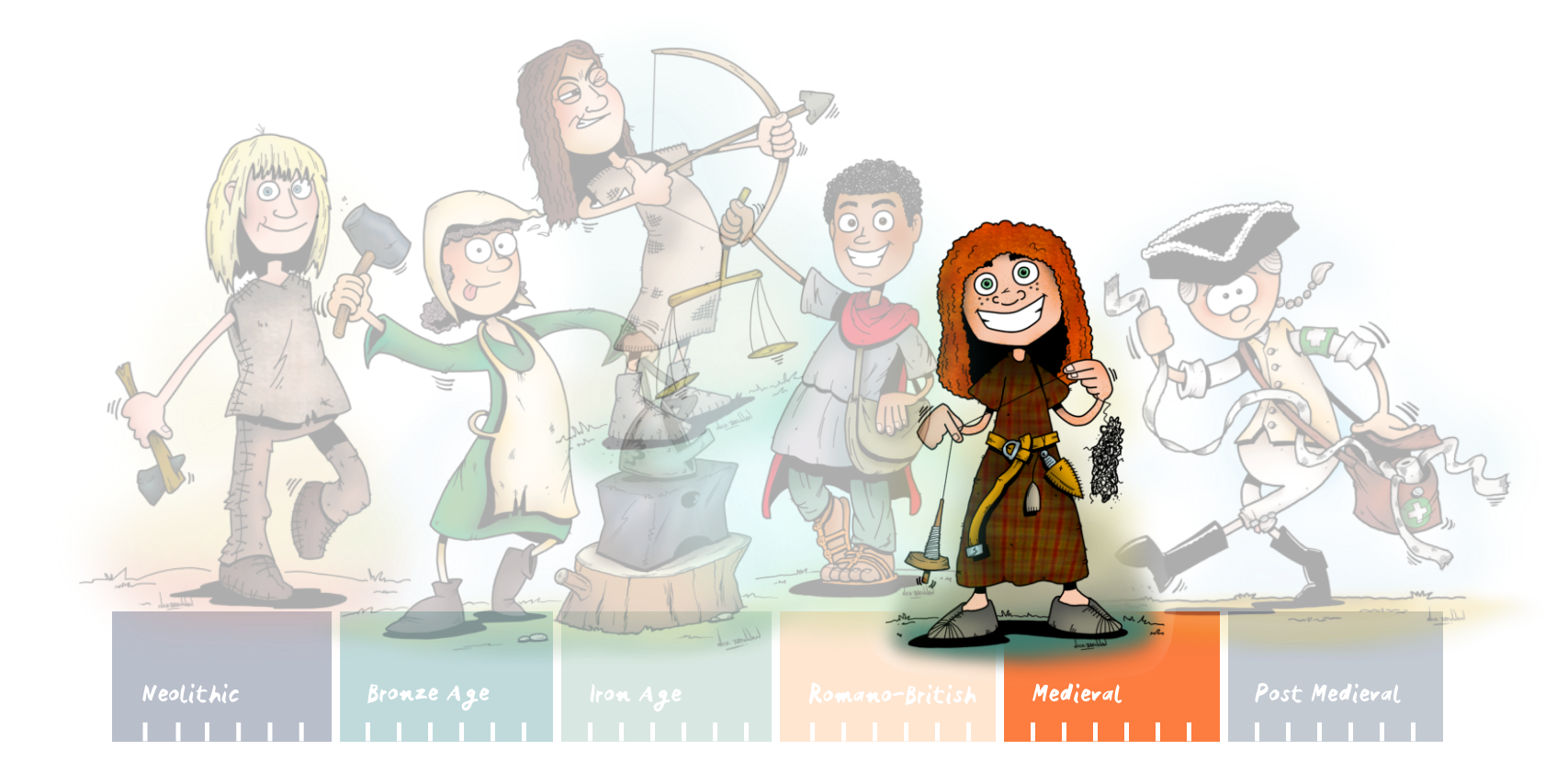

Castles, churches, and field systems shape the landscape; Cornish language and identity flourish amid Norman feudalism.

Period

Post Roman Britian was divided into small kingdoms and the southwest was still known as Dumnonia. The people shared close links to Brittany, Wales, the Isle of Man, Scotland and Ireland in similar language, religion and art. Early Christianity flourished as the ‘saints’ travelled around spreading their beliefs, with many leaving their mark in Cornish place names we still use today: St Neot, St Mawes, St Petroc, St Austell, St Just and dozens more.

Stories of saints are many and varied. St Ia (of St Ives) came over the sea from Ireland on only a leaf, and St Piran arrived floating on a millstone. Saint Felic had the miraculous gift of being able to communicate with lions, cats, and other feline creatures. Others were hermits, martyrs, and missionaries. Along with their legends, some have been honoured in tales of preserved relics or the dedication of monuments.

Christianity also brought literacy, and its kings are mentioned in surviving texts of the time. Latin and Ogham inscriptions appear in stone, along with carved Celtic knotwork patterns weaving together the magic of an older pagan culture and the new religion.

While eastern England was becoming dominated by the Germanic culture of the Anglo-Saxons, Dumnonia in the west maintained strong links to Brittany and Byzantium via the West Atlantic trade network to the Mediterranean. Traded tin brought significant wealth. Excavations at Tintagel have shown evidence of high-status feasting and exquisite goods from these far-flung connections.

By the 10thC, Cornwall retained its own identity and independence, its unique trade in tin, and the landscape was littered with larger settlements, mines, churches and stone crosses, with a catalogue of myths and legends to accompany them, including those of King Arthur.

From 1066, the Norman conquest of England enforced a new feudal system and the River Tamar became a border. Doomsday Book (an 11thC record of property across England) shows little of Cornwall was then owned by the Cornish, with the largest number of manors given to Robert, Count of Mortain – the first Earl of Cornwall (which in 1337 became a Duchy and was adopted by the eldest son of the reigning sovereign, as it is today). Robert built Launceston Castle which became so important, a walled town grew up around it. The biggest settlement though was Bodmin, with a population of around 1000 – only men are listed in Doomsday, so numbers of women and children are estimated!

Later, castles were also built at Restormel and Liskeard, and around 1280 Lostwithiel became the capital of the Duchy.

The worshipping of sacred springs became accepted by the church, becoming known as the Holy Wells that characterise the period; over 100 exist, many associated with their own saint. Perhaps these pure waters were further popularised as the Black Death hit Cornwall in 1349 with outbreaks recurring until 1352. Larger towns like Truro and Bodmin lost up to half of their populations.

The landscape was changed as granite was quarried and mining still boomed. Cornish tin remained internationally important; mixing with lead makes pewter, which was widely used. The tin industry brought great wealth to the Cornish aristocracy and provided employment for many in areas of poor farmland. The enormity of extraction changed the landscape in valleys, moors, woodlands and even the coast – the shifting of millions of tons of soil and rock resulted in the silting up of rivers and streams, creating new marshland and mudflats.

7 Monuments

5 Monuments

4 Monuments

4 Monuments